Lichens are generally overlooked as you pass along the coast or visit graveyards or walk among trees. They cover 6% of the earth’s land surfaces and they are press-ganged into a range of uses. Reindeer and caribou devour prodigious amounts of them. Humans consume vast quantities for perfumes, dyes, soaps and tinder.

All Images © Simon Robinson 2024

Available now from Bracket Books Ireland at outlets like FabHappy or WalkingCommentary.

While there are about 20,000 ‘species’ globally, as of January 9th, 2024, some 1600 types have been identified on the Hibernian and British Isles (according to the British Lichen Society). Over 1200 of these can be found in Ireland.

Lichens were long believed to be plants until microscopy revealed them to be a symbiotic association of algae with fungi. Lichens are communities of several different fungal species (mycobionts) in partnership with one or more algal species (photobionts). And not just that, recent studies reveal that adjacent but differing lichen types form guilds to assist each other, the algae building networks of relationships.

Humans are still considered to be animals despite the revelations from the Human Microbiome Project. Some say that there could be more than 1000 species of microorganisms living within any one human and many thousands more living among the global population. We walk around with more bacterial cells than human cells and our bacterial gene count exceeds the number of human genes by two orders of magnitude. Despite carrying 100 times more bacterial DNA, the bacterial mass is only about 100 grams. Yet without that 100 grams there can be no human. Scientists call it obligative mutualism when neither partner can survive without the other. Military folk call it mutually assured destruction in the case that cooperation goes wrong.

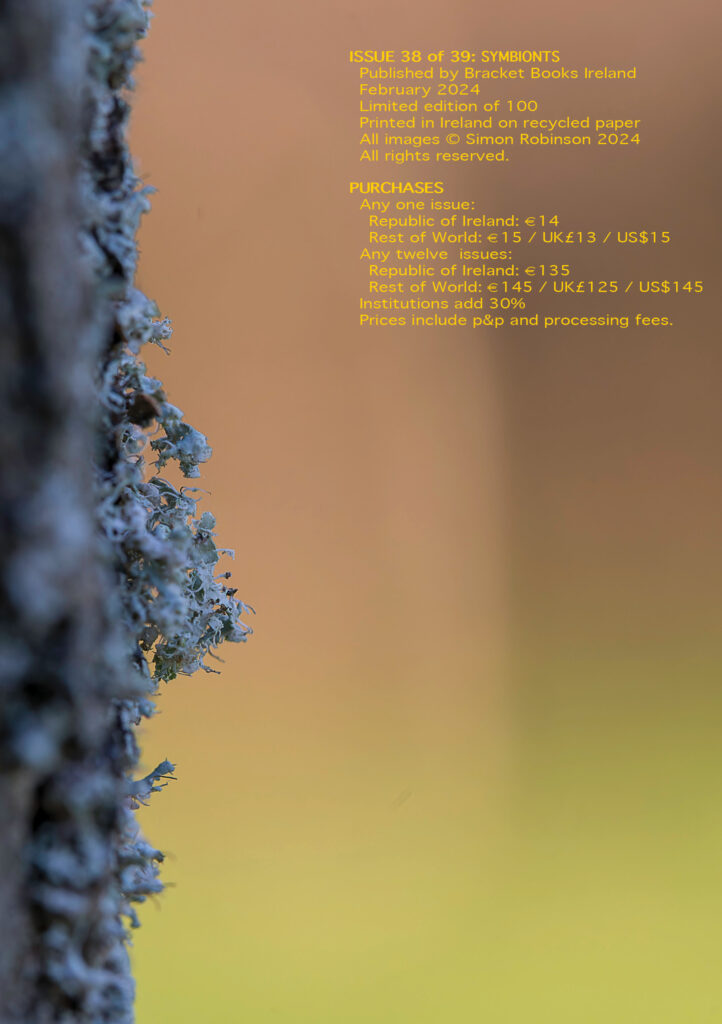

I’ve enjoyed the challenges of taking photographs of lichens and mosses for decades. They often appear familiar once magnified to human scale despite not being fractal. While lichens are colonies of symbionts, mosses live symbiotically on their hosts. Humans are symbionts though not living symbiotically with our host, the planet.

A walk in the forest prompts many questions: can I eat that? How do lichens propagate? What benefit does a tree get from hosting a moss? Why do obese human individuals lose micro-biotic diversity?

But perhaps we should question the notion of interdependence? Has the environment been affording lifeforms opportunities over geologic time? Has humanity already squandered 4 billion years of work because we failed to honour the complementarity between lifeforms and the environment? What return does a planet get from our existence?

Humans are genetically very similar. Trees are genetically diverse, both among and within species. An oak forest is composed of individuals that look much the same to us and yet each tree is genetically different. Stationary trees need such genetic diversity to adapt to local changes, else they all die. And lichens can live as long as trees: some growing in Scandinavia are at least 9,000 years old. It makes one wonder if the ‘spark of life’ is what is evolving in many forms, spreading to reduce the risk of extinguishment. Maybe the preservation of ‘life’ itself is the sole purpose of all living things be they lichens, trees or humans. Perhaps we humans are expendable?

Bracket Books printed chapbooks are available for online purchase through FabHappy but perhaps you’d prefer to enquire here. They’re published each calendar month, each copy uniquely numbered and posted at the end of each month. Prices include packaging, delivery, all currency and inflation risks.

Issue 38 of 39 – limited edition of 100/Published by Bracket Books Ireland

2023/4 SUBSCRIPTIONS

Chapbooks 25 to the final issue 39 (15 issues):

Republic of Ireland: €135

Rest of World: €145 / UK£125 / US$145

Institutions add 30%

Prices include p&p and processing fees.

I love this book. There’s plenty to think about and admire in here. It’s hard to believe this is your second last ‘zine.

Can you give us a hint about what you’ll do next?