I had an idea, a simple concept and like photography itself, it took years to be realised. My concept was that one photograph could be interrogated to reveal many stories, each distinct from the main image. Like a book has chapters, and chapters have paragraphs and sentences, the fractal potential of the image could be explored. It wasn’t dissimilar to creating and analysing geological cross sections with geophysical data, something I was involved with for most of my career. I like a challenge but creating Quarried, the April chapbook, turned out to be more difficult than I anticipated.

Available now from Bracket Books Ireland at outlets like FabHappy or WalkingCommentary.

The idea of quarrying a photograph was something I’d discussed with other photographers over the years. It’s become something we do all the time with satellite imagery and maps for navigation purposes. So why not for a vertical landscape? Time passed and now that I’m publishing a book a month, the right conditions existed to germinate the long-saved seed this Spring.

The kind of scene I needed seemed obvious. It had to be a historical site within which are lived many histories. The infinite potential for viewers’ imaginations could be piqued by imagery that represented both temporal and spatial attributes.

In academic language, the studium would be a tableau that allowed the viewer make historical, social and cultural inferences beyond the picture itself. Semiotic analysis, even if subconcious, would enable interpretations dependant on the experiences of the viewer. (I know this reads like trite twaddle but I don’t know how else to explain it.)

The baseline history had to be discernible and relevant. The depicted timescale would need to represent geologic and generational as well as current time.

The social and cultural elements would rely on serendipity. It would be a form of street photography restricted by landscape techniques and weather.

Capturing the scene would require some extreme technology. Managing the light is always a challenge, the sheer size of the image might become another.

The location had to be within very-old-dog-walking distance from our home. I knew I’d have to visit many times and several times a day. I’d have to test many scenes for content and light in order to establish the best view that was accessible to me with an aging Gus on the lead beside me.

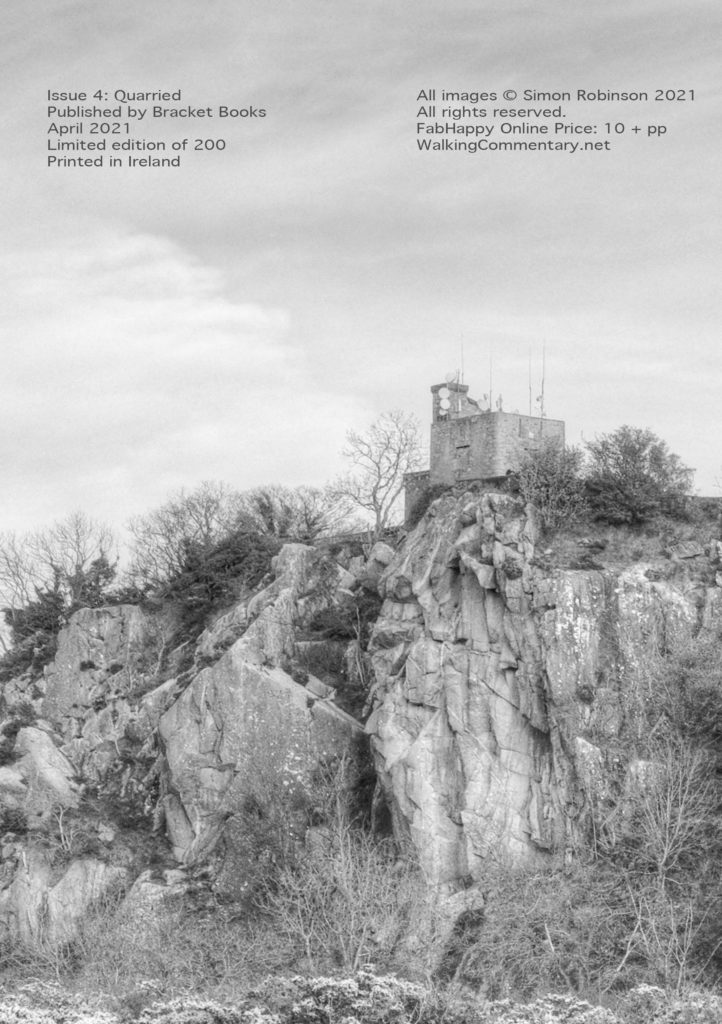

It dawned on me that the Dalkey Quarry was an ideal candidate. It’s barely a kilometre from my desk. The quarry was active from 1815(ish), around the time photography as we know it was being invented by brothers Nicéphore and Niépce. The main quarrying operations had ceased by 1867, at the height of the craze for the photographic miniatures (cartes de visite) that so poignantly outlive the soldiers of the American Civil War. Final closure of the quarry came in 1914 by virtue of being added to Killiney Hill Park. The fact that colour photography didn’t become affordable until Kodachrome was introduced in 1935 was further motivation to render this project in monochrome.

That’s when I realised my approach was being shaped by Roland Barthès after rereading Camera Lucida again last year. And I was designing a monochrome chapbook, under the influence of Michael Kenna whose work still amazes me. I can’t overlook the influences of Roger Fenton or Ansel Adams and Edward Weston and many, many more but I can’t claim they had a direct impact on the project.

The quarry had many other resonances. It’s an ancient batholith uplifted only to be scalped by glaciers. Four generations of labour then quarried, transported and reformed the rock. Climbers and dog walkers avail of the disused quarry today as sometimes do peregrine falcons.

to be continued …

Leave a Reply