I had to go to the dentist recently because a damaged molar needed attention. A week later, I returned to have no more than a few proud microns of enamel polished down in order that my jaw would close properly.

Jaws are truly remarkable things. Ask a jawless lamprey sucking on mud soup if they suffer jaw envy. Ask an oral cancer patient if they’d thought much about their jaws before calamity struck?

Teeth are also remarkable items. And of course the combination of jaw and teeth needs the complexity of neck rotation to function efficiently.

Most of us think about teeth only when they go wrong. I still recall with horror and sorrow waking from too little anaesthetic to find a dentist kneeling over my head. It was in Southern California in the heat of high summer. Air-conditioning couldn’t stop him dripping sweat onto me from the exertions required to remove an abscessed wisdom tooth. It was more impacted than the x-rays suggested.

There will be four wisdom teeth in the fifty or so you should expect over a lifetime. The wise know that continual maintenance of them all will pay dividends in later life. You might be able to enjoy steak in your eighties as opposed to relying on soup to get to ninety. And besides, the bacteria in the plaque you scrub away could significantly reduce the risk of heart attack. The daily scrubbing routine is perhaps a small price to pay for tools that enable you to eat several times daily for a century.

The faces of two of our grandkids are changing as they age from six to seven. Their deciduous or milk teeth are falling out and they appear different to us from one Zoom to the next. The gaps appear and the refill alters their facial structure. This change is known to us all, so commonplace that perhaps contact with the tooth fairy is the key to our taking note of this phenomenal event.

A great white shark can’t use a toothbrush so they have evolved a different strategy. They adapted to replace their teeth continually, perhaps enjoying 100,000 new teeth in their mouths over their lifetime. Some other sharks take less than a month to regenerate an entirely new set of gnashers. l mention the mouth because of course sharks have teeth on their skins too.

A question for biology researchers is whether the teeth were originally scales and if they evolved before the jaw, before the rotating neck. It’s an unresolved chicken and egg question. It’s a great mystery that will drive decades of doctoral studies.

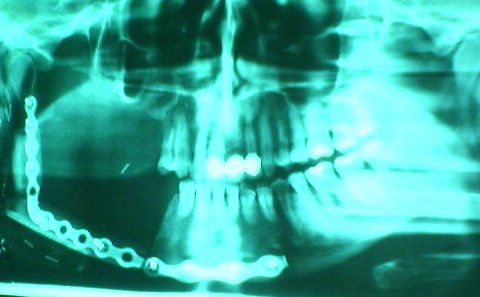

We’d like the answer quickly please. It’ll be far better for oral cancer treatments if we could grow a new jaw and teeth rather than engineer and embed a titanium replacement. And besides, the increasing acid in our diets and our expectation of ever greater life expectancy suggests that our teeth will need renewal half way through our lifetimes.

It’s 15 years since I read that scientists grew teeth in a chicken. It’s not as bad as you think. Birds used to have teeth until they discarded them some 80 million years ago. So the genes in embryonic chickens were manipulated to see if tooth growth could be re-stimulated. And it could. Which opens up paths to research on the potential reactivation of other dormant genes that might enable tissue regeneration to reduce scarring, for example.

References:

– Hens’ Teeth Not So Rare After All scientific paper

– The Evolution of Teeth podcast

– In Your Face memoir

– Word of Mouth – Coping with and Surviving Mouth, Head and Neck Cancers Dublin Dental Hospital

Leave a Reply