I’m fascinated by how one image can be manipulated to shape different stories. What is the essence of a shot given that there are an infinite number of photographs you can take from where you are reading this? Are there an infinite number of stories to be found in one shot?

735 seconds © Simon Robinson 2013

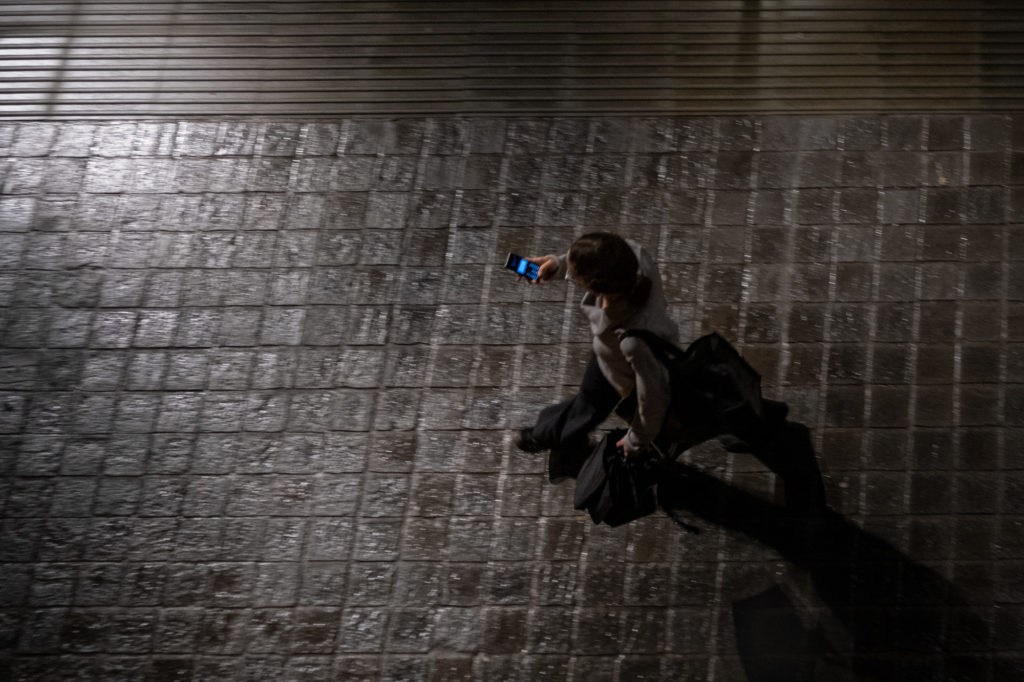

1/60 seconds © Simon Robinson 2019

I learned most of what I know about shaping stories with photographs from using my iPhone. The point of using the iPhone was convenience and efficiency. Always on, I could edit my photographs while walking and once edited, I could transmit the image from wherever I was. I didn’t think that people were following me (so to speak) but it forced a discipline on me. I could only use the tools and time available while hiking. I had to make decisions quickly. And then the next shot would appear, to be captured, shaped and posted. There are many examples of this form of story telling on my older blogs such as here in 2010, here in 2011 and here in 2017.

At one point, I had over 120 different Apps on my phone. It’s down to 49 apps now (I just checked) but I only use four or five with any regularity. My three favourites enable me to remove all of the colour around a subject of interest (Color Splash), render a photograph in greyscale with different tonal emphases (Noir) and finally, my iPhone photo workhorse is Snapseed. I got repetitive strain injuries using the various ‘touch’ screens as iPhone versions came and went. I wrapped ‘touch’ in quotes because Newton predicted that there would be an equal and opposite reaction to every gesture. It’s us that are touched by repetitive strains from pinching and flicking. As the Buddhists among you may already know, the sound of one hand typing is aarghh.

I have major applications like Lightroom and Photoshop on my phone too but they are unusable on the small phone screen.

So there you have it. I’m generally quite (un)comfortable acting as an opportunistic, street-style photographer with my phones.

While I don’t often scout my scenes and set-up for the perfect shot, I have, for example, planned shots months in advance and taken holidays to match my ambition. Once, I ended up standing among breaking waves on a freezing winter night with my DSLR camera on a tripod pointed back at a coastal railway. I was waiting for the ten seconds when the carriage lights of two passing commuter trains would illuminate the scene as they passed on the two tracks above me. I had anticipated the picture a few months before tides, moon and train schedules aligned. What I never considered was sharing the scene with a curious couple walking their dog. Understandably, she pointed a torch at my camera to see what was going on. I could hear their surprise at seeing someone standing in the lapping water ahead of them. They kept their torch shining towards the camera while they tried to understand what they were looking at. Their dog came over to sniff at the tripod and I called to them forlornly. The 90 second exposure was already ruined by their torchlight as the trains passed and disappeared into the night.

I went back a week later knowing it wasn’t ideal. The weather was better and there was no wind. I had recalculated the exposure because the timetables indicated the trains would pass me a few minutes apart. A new exposure time of about ten minutes would ensure I wouldn’t miss either train if they were delayed. It also meant I could use a sensor sensitivity of ISO 100 to minimise noise and and an aperture of f/16 to keep everything in focus. The two trains whizzed by a few minutes apart from each other, sometime in the middle of my ten minutes freezing on the beach. The changing rooms appeared in the foreground as I hoped they would but there wasn’t quite enough light to capture the detail from the middle-ground cliffs. That’s because the clouds that were reflecting orange-hued city lights from the the other side of the hill were replaced by stars that appear as ten-minute, comet-like streaks.

I used to have several lens kits for my iPhone but found that got in the way of making decisions. These days, DSLR in hand, I typically select and take one lens and hope to encounter scenes I can make interesting.

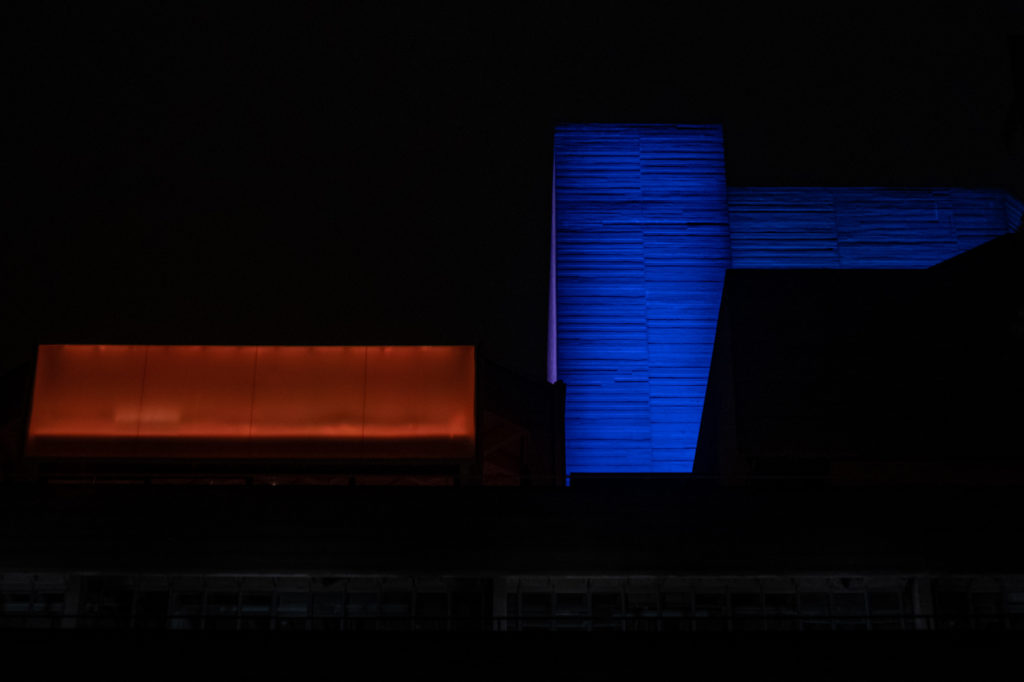

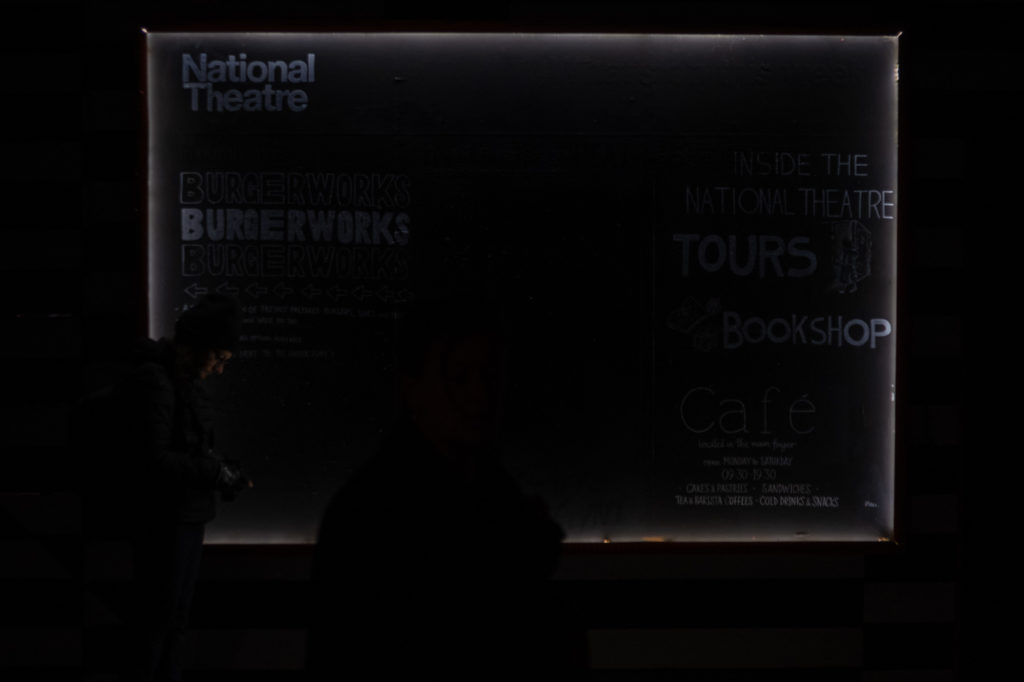

Edo Zollo gave a nighttime, street photography class a couple of years ago. So I signed up and walked around the South Bank in London with about twenty others for some three hours. We listened to expert suggestions from our teacher, snapped scenes he had scouted beforehand and reviewed our experiences afterwards. At the end, we had a huddle and were told to select our favourite one shot, display it on the camera screen and pass the parcel so to speak.

I was amazed by the different approaches I saw. It was the wide range of experience and equipment that allowed the most interesting, innovative shots stand out. A learner with a good eye took a great shot, a seasoned fifty year expert saw almost too many options and failed to impress. The best, in many opinions, was a minimalist shot of a shadowy but purposeful figure, isolated and yellowed by streetlight. It was of, not by, me. A superb shot that caught me unaware on a bare concrete stairwell. It needed no cropping, it was ideally composed and almost perfectly exposed. I wish I knew the name of the woman who took it and that I had a copy but we all parted in haste when people realised how quickly their enjoyable evening had passed. London’s last trains home don’t wait.

I was doubly pleased that a photo I took was rated next best. Not by everyone but by the tour guide and at least half of the group. I was in the right place at the right time to capture a woman as she passed below me illuminated by her phone.

I had an advantage in that I bought a lens specifically for the evening. Serendipitously, Mr CAD in Pimlico had a 35 mm manual Pentax lens on sale. We lived less than three hundred metres from Mr CAD, a delightful shop of photographic wonders that sometimes exercised my wallet. And so, I was shown the sixty year old lens as something that might interest me. It did and I happened to have the right adapter for my cameras since I’d bought other old lenses before. My advantage on the night tour was that I had a manual lens. My other classmates pointed high tech infrared beams with optical image stabilisers and struggled to achieve focus in low light. I had no choice but to manually select it and guess what, it really helped focus my brain on getting what was important into the frame.

All of these things and more came to mind today while I watched a Nigel Danson tutorial on my computer. He’s a photographer with almost 300,000 followers on his YouTube and Instagram accounts. I’ve watched a few of his tutorials and there’s one in particular that I watched again today. ‘What HAPPENS when 1000+ people EDIT the SAME PHOTO?’ I think you’ll agree that the answer is quite fascinating.

Leave a Reply