Yeasts as carbon dioxide strippers. What a concept! Suddenly you are thinking of National Collection of Yeast Cultures in Norwich or the Center for Bread Flavour outside Brussels? Wrong countries. I’m thinking of Austria. But first, we’ll need to go to the UAE, Oman and Cyprus where you might be able to see rocks soaking up CO2.

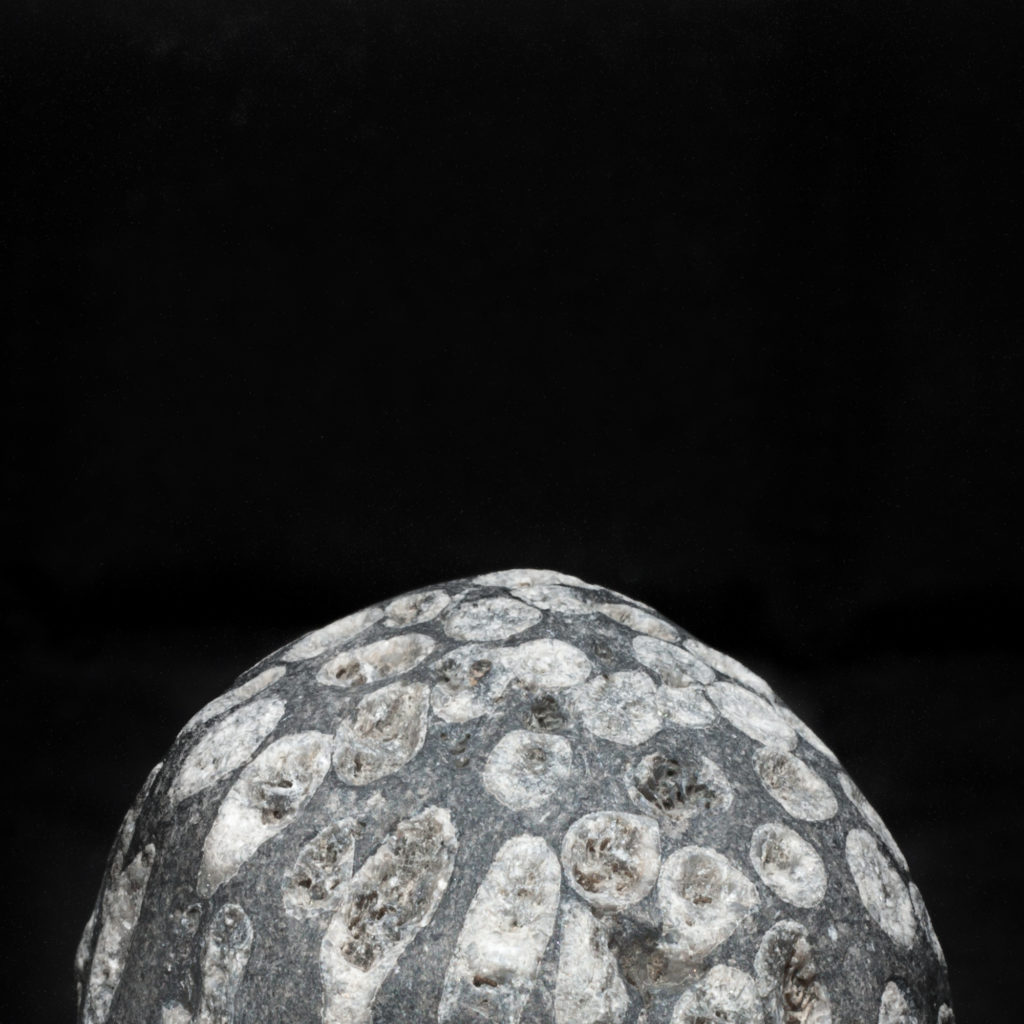

Having trained as a geologist, I’ve since encountered vast amount of limestones and related lithotypes that are deposited across the globe. I’ve had the benefit of geophysical tools to peer ten kilometres deep into the subsurface, and I can tell you that the surface carbonate coverage is a very misleading. It shows but a small fraction of the total amount held in sedimentary basins around the planet. These lime-rich rocks are effectively carbon sinks. That’s to say, they are one of nature’s best carbon capture and storage devices. They are generally made from the remnants of decaying marine organisms. You will have seen these as fossils of the skeletons of corals, foraminifera and molluscs. They are often visible to me among the grey pebbles that litter Ireland’s beaches. Chemically, these rocks are predominantly carbonates of calcium and magnesium. Nature somehow ‘knew’ of the need to sequester carbon hundreds of millions of years before we ‘learned’ that we’ll perish if we liberate it.

Since your body is mostly water but also 20% carbon, you might be interested in a few carbon facts. You may not have heard of the Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO) but whether you have or not, let me say that the DCO have uncovered a few reasons to be hopeful, even cheerful, about the future state of our planet.

In essence, the DCO spent ten years looking into the carbon cycle. No one is saying this discovered Planet B but there most certainly are some new lights to guide us through the tunnel towards the future.

[You might spend a few minutes with Stephen Leahy on the National Geographic site after you leave here. I’ll put that link and a few others at the bottom of this journal.]

One of these is that ophiolites capture carbon. I’ve walked the Semail in the Hajar south of Khor Fakkan and strolled over the Troodos. Indeed, I drove to Hajar Mountains to see the mysterious ophiolite. More elliptically, I took the family to see the Troodos precisely because it is an ophiolite complex. I did both these trips because ophiolites had a romance to them, a romance that probably only appeals to geologists.

‘Ophiolites were not widely accepted by English-writing geologists until the late 1960s.’ wrote Yildirim Dilek in 2003 in A personal history of the ophiolite concept. I heard the great Fred Vine talk in Trinity in the mid 1970s sitting among a few late deniers of continental drift. And there was Vine talking about vast chunks of ocean floor rock that had been scrunched up to the surface for our investigations. No other explanation for them seemed plausible. They were pushed up at the points of collision of drifting continents. The rocks contained mineral assemblages associated with oceanic crust and the upper mantle. I knew there and then that I had to see them. And by coincidence, within three years, I was in the UAE at the boarder with Oman walking over the Semail Ophiolite in the Hajar Mountains.

Now I read of carbon capture that ‘One of these sequestration methods involves a large slab of rock pushed up from Earth’s upper mantle long ago in what’s now the country of Oman. Known as the Samail Ophiolite, weathering and microbial life inside the rock take carbon dioxide out of the air and turns it into carbonate minerals.’

In the UK, you may know that National Collection of Yeast Cultures stores hundreds of thousands of strains of yeast. Yet some scientists think that mankind knows of no more than 5% of the the yeast that exist. Over in Austria, researchers like Thomas Gassler et al wondered if yeasts that exude CO2 could be persuaded to ingest it. A bio-engineered yeast Pichia pastoris strain is being studied for it’s potential to ‘promote sustainability by sequestering the greenhouse gas CO2, and by avoiding consumption of an organic feedstock with alternative uses in food production.’

They’re hoping to patent this path to Planet B.

I knew a man who owned the island he lived on. Several kilometres offshore, he owned everything he could see. When Fred Vine talked of continents drifting, he was elaborating on the conclusions drawn from decades of observation and thought. Would a man who lived in isolation on an island have much use for such concepts? In fact, he did. He was fascinated by such thoughts, to the point of engaging with the Professor of Geology, Chris Stillman, to study and explain how the island fitted into the grand scheme.

Even from our isolated positions of viewing, we can see bigger pictures if we allow ourselves the freedom to imagine. And so it should be with climate control.

I believe that planetary climate control is within our gift. I don’t know if yeasts or ophiolites are a main story or just a few sentences in the narrative. I do know that there is too much carbon in the ground and in the atmosphere if we are to survive.

The alternative solution might be to resign ourselves to a bionic future.

Further Reading Links:

The Sourdough Library in Brussels.

National Collection of Yeast Cultures in Norwich.

The industrial yeast Pichia pastoris is converted …

Leahy summarises Deep Carbon Observatory conclusions.

How much carbon is there on the planet?

Easy reading wiki on ophiolites.

Fred Vine and Drum Matthews changed geology with the view from the shoulders of Wegener, McKenzie, Morley, Hess, Wilson and many more.

Leave a Reply