‘Rosebud’ was an enigma: the dying word of Citizen Kane, finally explained at the end of the film. Similarly, there was a Rosmeen question that came to be resolved shortly before our father died. As Orson Welles wrote in 1975, denying that his Kane character was modelled on media tycoon Randolph Hearst ‘There are parallels, but these can be just as misleading as comparisons.’

I don’t think that Rosebud and Rosmeen have parallels other than that they were words uttered by dying men. The first rose is fictional, and by comparison, the latter rose-like word turned out to be real.

‘Have you been down to see Rosmeen?’ said my father.

He’d spent his last months in a local nursing home. Today’s journal won’t recount any of the difficulties that all involved experienced during his failing years. It may well be that there’s a tale for another time but for today, I’m focussing on the relentless cognitive impairment that was really sad yet often illuminating. It’s the latter that inspired today’s thoughts and journal.

Until I read Livewired by David Eagleman (2020) I had been fascinated to have noticed that memories are altered by their recall. Now, after a science update, I think it’s plausible that our brain reshapes itself all the time. It’s not the memories that change, it’s the brain adapting to the memory.

Back when my father was dying, I was commuting weekly from Dublin to work in the UK. I saw him most weekends in those last nine months of his life, as he faded in the nursing home. This commuting pattern meant I saw him episodically. I was seeing him change by stages rather than continuously. Digital not analogue, so to speak. I saw the changes in cognitive ability as if he was methodically going down a flight of stairs rather than slipping quickly down a garden slide.

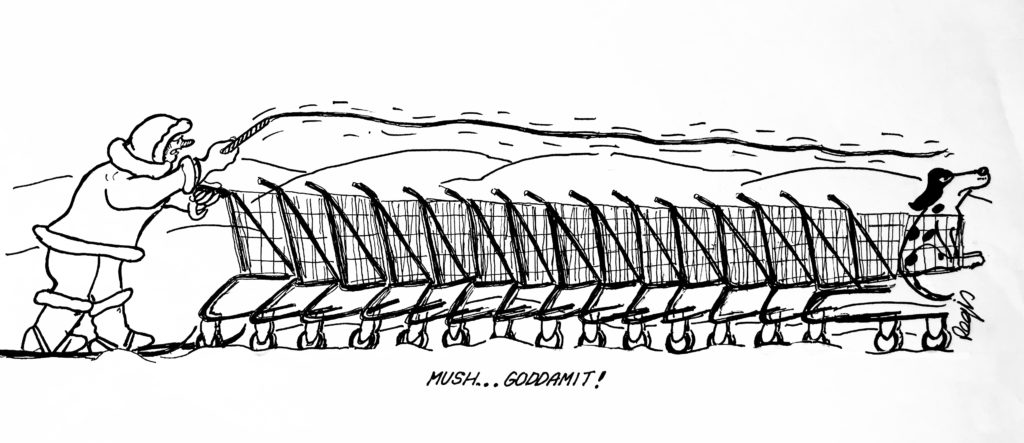

He had moments when he couldn’t remember what he used to do. Film-maker. Chef. Author. Cartoonist. He sometimes seemed to forget that he was also a grandfather, father, husband and son.

There were times that he’d be very alert and we’d talk about the family. It changed after a few months into his nursing home stay: his connections to family members became increasingly tenuous. At first, we hadn’t noticed because, as visitors, we tended to do the talking. We were updating him with news and gossip. Slowly it dawned on us that he wasn’t sure who we were talking about.

The first to fade were the recent memories of his great-grandchildren. Even when they had visited, there seemed to be some uncertainty as to who exactly they were. Then, perhaps a month later, their parents went beyond his grasp despite the abundance of once familiar faces in photo montages on the wall above the headboard of his bed. His wife, living across the wall in sheltered accommodation, their two offspring and their spouses didn’t so much fade as become ghostly presences in his mind. Talismanic rather than totemic, he seemed comfortable talking with or about them. Except that he’d tell me, for example, how I was getting on in London. One story was an elaborate version of my trying to sell my London flat ahead of an office relocation. I’d told him about it several weeks before, so his short term memory hadn’t completely failed. For him, we were very much in his thoughts and perhaps our physical presence had become indistinguishable from our virtual manifestations.

Only the week before he’d been asking how the house looked. It took me a while to realise that he was referring to his mother’s house. A house that was sold after she died, some forty years earlier. A family chore had been to cut her garden grass every week in summer, something I hated because of the cups in which she’d give me tea. Her eyesight wasn’t up to seeing whether the cup was washed let alone clean and guests couldn’t tell what lurked beneath the surface of the near black tea. Now he wanted to know how the garden looked, as if I’d just cut the lawn. Two quite different manifestations of old age.

One Saturday in late January, I stopped by so we could be together to watch Ireland playing rugby on the TV in his room. For him, it was another pyjama day as his days of dressing and acting communally were decreasing in frequency. Though he seemed to be enjoying the game, he stayed under the covers of his bed, not quite as engaged as had been usual. He fell in and out of sleep at random times and would ask about who was playing when he woke.

At one point, towards the end of the game, he pulled himself up in the bed, agitated and with great effort tried to swing his legs as if to leave the bed. He wanted me to help him dress before they got there. ‘Who?’ I asked.

‘Who else are you expecting?’ I repeated.

‘Jack and probably Pop’ was the surprise reply. His oldest brother Jack was dead fifty years and Pop, his father, five years longer.

I explained how they couldn’t be coming that day and though he was disappointed, he relaxed, still thinking about them, believing they’d be by soon enough.

He told me how he’d been to Galway recently and had pulled over to look at the building site of the new cathedral. He laughed about Bishop Browne putting a cathedral in the prison, a joke that passed me by. I hadn’t known the cathedral was built on the site of an old prison, something that might have been common knowledge in our family given that Pop, his father, was the architect on the project. To be fair, the address is Gaol Road so I could have guessed.

He was simply reliving one of many journeys to Galway, a county where we all spent a lot of time freezing cold on and around Lough Corrib. Trout fishing was an agnate family passion, more an affliction if you ask me. I sensed he was smelling the odours of a lakeside cottage in the early sixties, which I presumed would be the tobacco smoke, damp wool, mould and turf smoke that I recall from my nights spent in the room the extended family called Little Hell.

A few weeks later, I noted that my father had regressed even further.

‘It won’t be long now’ was something I’d heard from the staff each week for months but this time, I knew it was finally true because it was said in more hushed, empathetic tones.

In his room, we spoke a lot about a trial and the inconvenience of living in hotel rooms for months on end. I realised that he was back in the 1950s, to a time when another of his brothers had been called to jury duty. He ended up sequestered for months during a murder trail. My father was gossiping like he might have done over a pint or two in a pub at the time. Except that he lost the thread from time to time, almost as if the two pints had become six with a few chasers.

By now, I wasn’t sure that my father knew who I was. We’d been slow to cop on to the fact that he’d been very good at pretending he understood things for the last five years. He had masked his increasing dementia very well. So well it turned out, that he was exploited by officials of the State’s revenue collectors and later, he convinced district nurses and social workers of his capacity to live at home.

Another two weeks went by before I could visit again. He seemed certain that I was his brother Jack for a while until I became his father. Then he switched to telling me how angry his mother had become when brother Jack came home from the Army. Serving in the army meant he’d been able to supply the family with staples and exotics beyond the wartime shortages and this had suddenly stopped. There’s a bigger story here too. The Army in question was the British Army and they were at war for the second time in Jack’s life.

And so it was that I went back to London for a week, returning on a cold, early March Monday, the day of his last birthday. It was also the last time I would see him. And that’s when Rosmeen came up.

‘Have you been down to see Rosmeen?’

‘What?’ I asked.

‘Don’t you remember the bombs?’

At first I thought he meant the paramilitary bombings in the centre of Dublin in 1972 and 1973.

We groped around for connections for a short while until he gave me the clue I needed to join him, now aged 11, back in the winter of 1940.

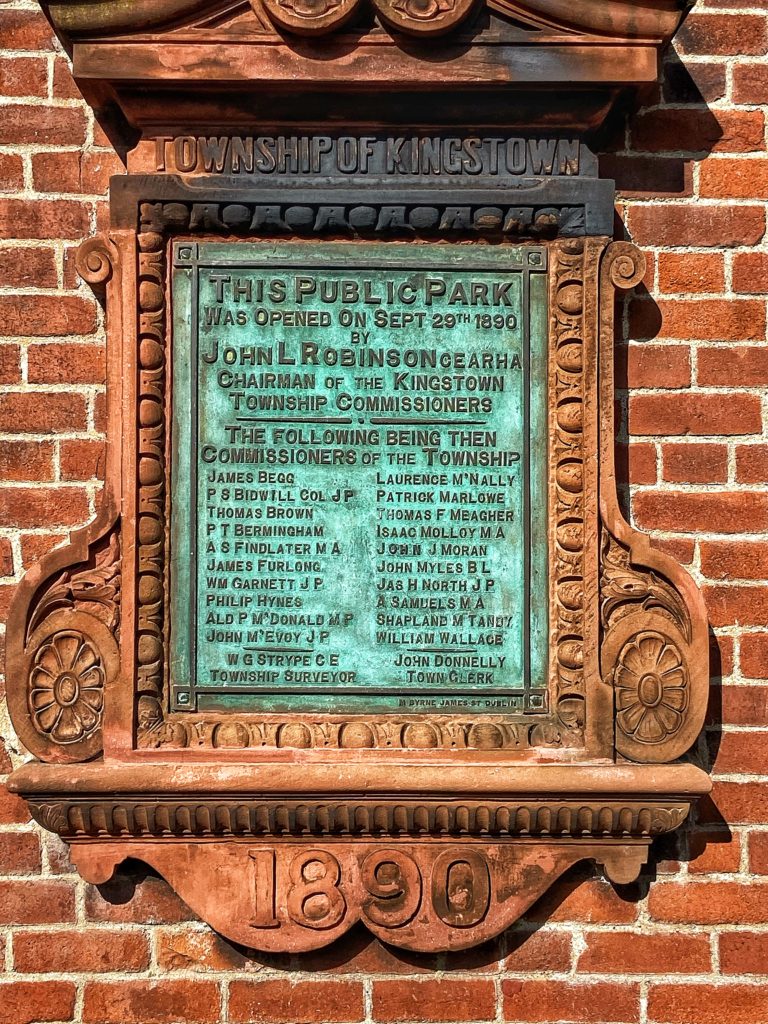

Then I remembered that he’d once met us on a family outing in The People’s Park in Dun Laoghaire some twenty years ago. Our kids were on bicycles, safely travelling the paths in the park. He’d proudly shown the kids, his grandkids, the plaque that commemorates the opening of the park in 1890. The Chairman of the Kingstown Township Commissioners was their great-great-grandfather John L Robinson, another architect. My father also told them that across the road, when he was their age, was where the Luftwaffe had bombed Dun Laoghaire thinking it was Liverpool.

Just two bombs were dropped. One of them landed between Rosmeen Park and Rosmeen Gardens at 1930 on Friday, December 20th, 1940, under a waning, gibbous moon.

The latest neuroscience research suggests that memories are perhaps ‘a stream of new neurons being born in the hippocampus and tracking their way into the adult cortex’ according to David Eagleman.

I guess that what we witnessed in my father was the gradual failing of his hippocampus and the reemergence of long hidden neurons from his cortex.

Rosmeen.

Can our memories be broken down to just a few cells or connections of neurons? It seems rather implausible and distinctly lacking of any drama. I can’t imagine a surgeon of the future excising a small piece of squidgy brain matter and saying “that’s their memory of the summer holiday of 2015”.

It’s sad that our bodies and brains start failing later in life.

Recent opinion holds that the brain’s neuronal storage system is both distributed and contains redundancies. Some have posited that our genes can be modified by our experiences. I think this is very dramatic indeed. Have you read that human brain structure has been recovered from a vitrified Pompeian head? Gruesome yet it may provide a view back 2000 years.

And I agree on the sadness of my senescence that’s well underway but for now, I’m enjoying the delusion of apparent wisdom.