Yesterday morning, I shaved off my pandemic beard. It was a sunny day with a slight breeze so I took myself to the garden and trimmed it before wet shaving it clean. Not that you care to know such stuff but there it is, I did it.

And yesterday afternoon, I noticed new boreholes in our weeping willow. You know, the kinds of holes you’d assume were woodworm if you found them in your antique table. I sawed off a slice from a branch I’d pruned and paint-poisoned a couple of years ago.

There were some minor unintended consequences for both of these relatively trivial actions. I learned some minor lessons too.

The first of the consequences arose while I was still trimming the weeping willow. Others, sitting in the garden enjoying the sun, had good reason to complain about the cloud of dry sawdust I couldn’t see was blown to where they sat on the other side of the tree. Continuing to be focussed on my task rather than their discomfort, I proudly showed them the grub I found in the base of the borehole. You can imagine they didn’t see how that justified my coating them in sawdust.

I may have disinfected a tree but without maintaining my vigilance, a clever insect overcame my defence. And in defending against the breach, more disruption was spread across the region. The cave of Osama bin Grub, I thought.

And the second consequence became apparent today. I had dry shaved without my glasses; I shaved blind, so to speak. Now I know that some of the grotty trimmings were transported to a bathroom floor on the clingy T-shirt I chose for the great shave. Sure, a bit of vacuuming solved the problem where I could see it. The question is where else did I not see it. And while I may have shaved myself clean, there was some careless action that needed unplanned remediation in the future.

Few readers will see any reasonable connections in these uninvited observations of daily life. However, I’ve been re-reading Pankaj Mishra’s Age of Anger and doing so slowly this time. I don’t have the fast version of reading comprehension and there’s so much in this book that needs time digest. I admit that I use analogy to help pare new concepts to the barest of bones to facilitate uptake; and yes, I recognise that the feathering of dinosaurs was impossible to demonstrate from their bare bones.

Key to all of this is that there are always consequences to our actions. Proportionality is not always comprehended by the instigator. Timing is just one of imponderables. Selling double-decker buses to Iran might seem like progress to a sales team. In the short term, lots of political clout comes from big export orders. Some fifty years later, the buses remain a potent symbol of condescension, pillage and much, much more. Things change. Now Iran is said to be ramping up its nuclear capability. I’ll bet there are still people annoyed at those buses.

I picked on Iran for this apologue because it’s clear that a new order was pushed on them in someone else’s vision of progress in the 1950s and 60s. The enforced new order did not account for the creation of new alienations and new inequalities. New orders never do, especially those pushed from benefactors and external sources with opaque agendas. Such opacity is generally assumed by the recipients to be a mask for some skullduggery or other. The new order may be welcomed by some but it is perceived as a threat to many more.

You can’t just demand clerics be clean shaven and ignore those who wait it out in caves. At best, there’s a short term gain for the sellers of the new order. A seller, the British MP Bruce-Gardyne wrote that double decker buses ‘looked surprisingly at home under the blue skies of Tehran’. Hegemony is a two way street, given time.

Today’s news of toppling statuary to slavers seems a different thing entirely. Or is it? I’ll leave that to the reader.

These are not the deep thoughts of informed philosophy. After all, I’d much rather be walking than journaling.

We had a masked cleaner in the house today. It’s her livelihood and we’ve not seen her since February. She admitted that these last few months without work have been hard for her. It’s all too easy to overlook people like her in today’s circumstances and it seems that most did.

Our neighbours had a garden dinner party that wrapped up at 1.30 this morning and their neighbour’s builders started sawing and hammering at 7.10.

So I’m missing some of the lockdown deprivations. I’d definitely much rather be walking than journaling.

I’d like to finish on time.

I have no idea who owned a cheap 1930s wristwatch before me. I wore it with pride for a year when I was nine or ten. I think it was a gift from my parents but where they got it, I don’t recall. It came to a bad end when the glass and the hands broke in the inevitable kind of accident that befalls an eight year-old wearing vintage wristwatches. It was my pride and joy because it glowed in the dark. I used to keep the watch on my pillow as I went to sleep; it’s phosphorescent glow was simply mesmerising and more reliable than the cheap mechanism that drove it. It was reassuring to a kid to see its glow was alive and looking after you even in the smallest and darkest hours of the scary night. Radium made it safe to close the bedroom door.

I loved reading biography and spent my first two years in boarding school reading every biography I could find in the rather well endowed school library.

A biography of the Curies was one of my favourites. The idea of boiling ten tons of pitchblende ore tailings over three years to acquire a decigramme of something you didn’t know existed in order to prove that it did was heady stuff. The determination. The obstinacy. The confidence. The challenge. And that it was quickly found to make diamonds phosphorescent so that imitations could be exposed was just brilliant. Other benefits were less salutory. It was added to chocolate to promote good health. It was sold as the Raithor suppository. It was made up as a radiencrinator, a virility aid for men. I knew the of the cancer treatment benefits but somehow fixing something dreadful isn’t as compelling to the 12 year old mind as the learning of unmentionable terrors. The news cycles are always driven on this basis which begs a question of the mental age of the news purveyors.

My adult self now knows that when Marie Curie died of aplastic anaemia from exposure to radiation, whoever had painted my watch face was probably realising they were poisoned too. The glow-in-the-dark faces of the sadly famous ‘Radium Five’ girls had by then been morphing into the disfiguring cancerous tumours that killed them. Even Marie Curie had her first ulcer by 1900.

There’s a book by her daughter Ève Cure called Madame Curie (1938) that my 12 year old self recalls was worth the read. Which reminds me that Marie Curie’s cookbooks and diaries are still radioactive.

And since this journal was to be about time, let me say that once upon a time I quit my first real job when the face of my Casio digital wristwatch clouded over. At first I thought it was the summer heat in Sharjah that did it. Then I drank some mercury with my coffee which prompted brief thoughts of industrial safety. A few weeks passed and the fume cupboards of another of the company’s laboratories went on fire. We too used the same cheap extractor fans in our lab and I got worried. And eureka, after a slow dawning, I realised that my watch had started to cloud over before we got a fume cupboard, in a time when the Soxhlet apparatus was open to the room where we worked.

The Soxhlets were used to boil solvents like toluene and sometimes xylene to dissolve oil residue from rock samples. Once the organics were removed from the rock, we could measure the true pore space in the samples in order to determine the quantity of fluid the rock could hold. Think of the rock as a hard sponge. Imagine injecting mercury into pore space and oops, get the sequence wrong and there’s mercury bouncing off the ceiling and falling into your coffee. And there’s a story for another day.

Fume cupboards featured in college too. We were making hydrogen sulphide, as you do in university Chemistry 101, and the fan failed to circulate the air. H2S is the bane of many oilfields. One of the more immediate challenges is that it’s heavier than air. Another is that it renders humans anosmic so that you can’t smell the hideous signature smell of rotten-eggs and die of respiratory tract failure after passing out while standing in a gas invisible to humans. As the manuals say, ‘high concentrations of hydrogen sulphide can produce extremely rapid unconsciousness and death’. That day in college, I recall that the stench was horrendous when we re-entered the room from which we had been evacuated. We’d not smelled it when the fume cupboard failed. Serious lesson learned.

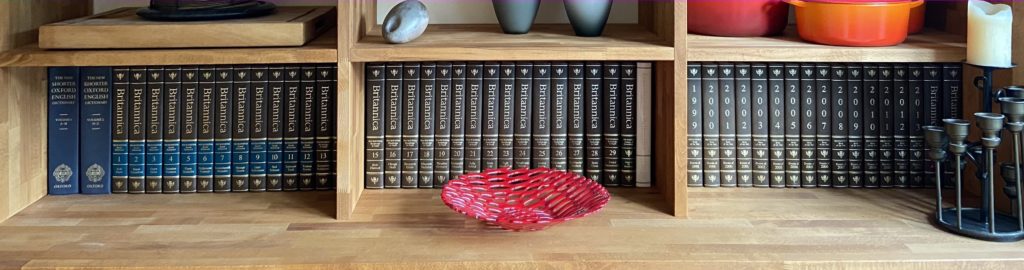

Two books worth having in your back bathroom if you don’t already have Encyclopaedia Britannica in your kitchen:

Periodic Tales Hugh Aldersey-Williams (2011)

The Periodic Table Paul Parsons & Gail Dixon (2013)

Leave a Reply