It’s amazing what you get done in the bath. That was my takeaway from the movie Trumbo, based on the true story of a blacklisted script writer accused of using movie scripts as communist propaganda. And I latched onto the fact that he wrote in the bath! Maybe that’s because baths and saunas, like walking, are activities that bring me great clarity of thought: a transient clarity borne of an intense but narrow focus. Wabi sabi?

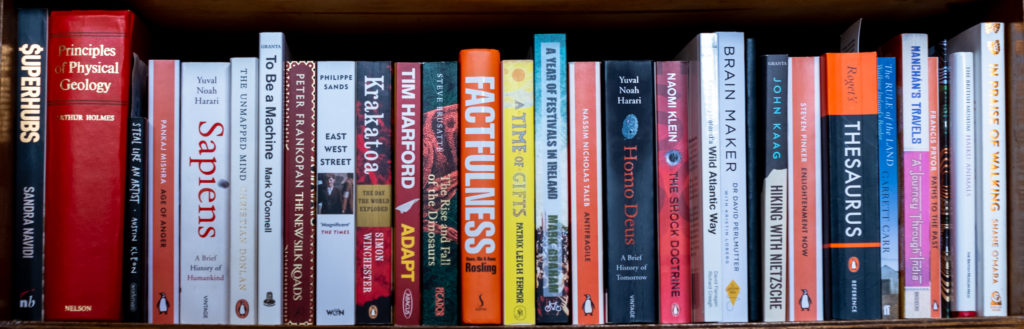

When Catherine Dunne was honoured with the 2018 Irish PEN Award for Contribution to Irish Literature, I was lucky enough to be in attendance. A round-table chat about the books we were reading that year brought me to the realisation that, sitting among so many novelists, I had read no fiction in the previous twelve months. I’d unexpectedly retired from a career in geoscience and possessing a past and a present, I was looking for a future. Determinism was parked and I was imagining multiple probabilistic outcomes while trying to make the right choices. My bedside bookshelves were decorated, if not vertabrated, with spine words like Harari, Sapiens, Syed, Black Box Thinking, Taleb, Antifragile, Frankopan, The New Silk Roads, O’Connell, To Be A Machine, Rosling Factfulness and walking here, there and anywhere.

I broke my own spine when I was 18. I regained consciousness after a fall from a tree, alone and paralysed from the waist down. I pulled myself along the ground for twenty minutes until I felt pins and needles in my feet. The relief wasn’t as palpable as you’d might expect and I went out to the pub afterwards as a pillion passenger on a motorcycle. It was seeing the x-rays the following day and our GP’s blood-drained face that educated me (I’ll keep that story back for another chapter).

Many months lying on a board followed and thereafter, I spent a year in a shoulder-to-pelvis brace. Those months on the board brought a girl through the bedroom window who became the woman who married me. A friend coming to visit me drove his motorcycle into a tree and I was unable to attend his funeral. A cousin thought it helpful to bring me porn magazines from his holiday in Sweden. He also gave me Chariots of the Gods, the best-selling book by Erich von Däniken that alleged aliens taught us most of what we know. However, there was another book that changed the direction of my life. A family friend gave me a second-hand copy of Principles of Physical Geology by Arthur Holmes. My broken spine redirected many of my futures.

I mentioned in an earlier journal that the Physical Geology book made me become a geologist. Like a rock, it was very heavy to hold over my head that supine summer but it was more exciting reading than the Swedish porn or the Chariots. I had already been an avid reader for a decade yet couldn’t imagine how 200,000 people could have died in Kansu in 1920 and maybe worse, another 100,000 killed in 1927 by ‘catastrophic landslips of loess which overwhelmed cave dwellings, buried villages and towns and blocked river courses, so causing calamitous floods’. People still lived in caves? Or how in 1929, the Cotopaxi eruption fired a 200 ton boulder nine miles across the Andes. Maybe that’s why I’ve climbed Vesuvius, Krakatoa and many more volcanoes. Holmes wrote of places where people dropped dead when the wind changed. Just the other night, there was a TV documentary about the Nyiragongo volcano that poisons people around Goma with emissions of invisible carbon dioxide. A horrible situation since Goma is a growing centre of refuge from perennial war, where people try to eke out a living, knowing that deadly fast moving lava flows are coming one day soon. I’m guessing the equally invisible Covid-19 will get there first.

von Däniken’s assertions seemed ridiculous even to me in 1972 and were dismissed by science and history. Holmes, on the other hand, had originally dismissed the principles of continental drift as ‘purely speculative’ but completely revised the book in 1965 to embrace the new scientific learnings. Arguably, I’m relating tales of misinformation and the precautionary principle in action. People really did argue with me that because they’d read about the aliens, it must be true. And I learned that the greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge (the quote itself an example of how misinformation might work: it was from Daniel Boorstin despite people wanting it have been Stephen Hawking).

Back in 2018, I was teaching some kids about geophysics. I digressed into doveryáy, no proveryáy as I told the group of 16 and 17 year olds that they were ignorant. ‘Trust, but verify’ I implored. I demonstrated their ignorance to them, a very bright group with high expectations of themselves. I used some of Hans Rosling’s Factfulness questions to which they gave the predicted answers – that is to say they got less than 30% right, just like our world leaders in Davos before them. I said that I thought it was Stephen Hawking who posited that what’s taught in science class is already out of date, so whatever I said about geophysics technology was already changing. We had a lunch a few days later and some of the kids joked that I was the guy who told them they were ignorant. One shared how angry his parents were to hear that some corporate scientist had mocked their child. He told me he was still planning to be an accountant and asked if I minded that he used my version of the test on his parents. He said they scored the same as him and that he thought they’d learned something important.

Keep reading. Keep learning. And remember, Rosling taught our world leaders that they suffer the illusion of knowledge but they didn’t understand him. Aren’t we all imperfect, impermanent and incomplete?

Spine words

Wabi Sabi? Spine words dragged into memory at 1 metre per second.

Weed or flower?

Leave a Reply